|

|

| Oracle v. Google - Pre-Trial Filings - Part II - mw |

|

|

Tuesday, October 11 2011 @ 04:00 PM EDT

|

Today we turn to the rest of the pre-trial filings made last Friday and, in particular, to the motions in limine made by Oracle. As with Google, Oracle was limited to five such motions. Several of the Google motions could be anticipated, but the same cannot be said for most of the Oracle motions.

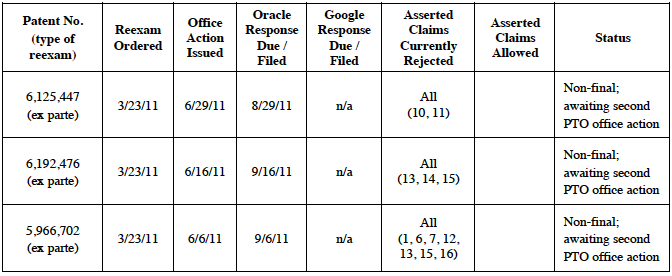

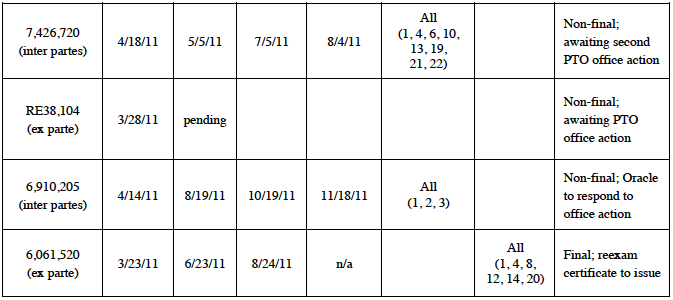

The first Oracle motion seeks to exclude any reference to the reexaminations now pending before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to the extent those reexaminations are not concluded. Of the seven patents at issue in reexamination, one reexamination, that of the '520 patent, has been completed and a certificate of reissue has been granted. The remainder of the reexaminations are still pending.

Oracle is justified in seeking to exclude the non-final reexamination proceedings because such proceedings are not binding on the court until they are final. Consequently, the court may take up issues of invalidity with respect to each of the patents and, unless a reexamination has been made final and a reissue granted, the court is free to make its own determination as to validity based on the patent as originally issued and asserted.

With one exception, this motion should not be particularly problematic for Google as its invalidity contentions pending before the court are the same as those pending before the USPTO. The exception lies with any amendment that Oracle may voluntarily enter in order to overcome a rejection by the USPTO. To the extent such an amendment is offered by Oracle, regardless of whether it results in a conclusion of the then-pending reexamination, Oracle should be bound by the amendment and Google should be permitted to offer the amendment at trial.

The only other concern with this first motion if it is granted as requested is that Oracle will have every incentive to prolong the reexamination process to assure that no further reexaminations are made final before the trial concludes.

The second Oracle motion seeks to exclude Google from asserting, as a defense to the charge of willful infringement, that Google relied on the advice of counsel in determining that it was not infringing either the Oracle/Sun copyrights or patents. Oracle contends that Google has placed no such advice into evidence and, further, that Google thwarted attempts of Oracle to identify any such advice. On its face, this motion would appear to be reasonable.

One problem with this second motion is the time frame upon which Google is alleged to have been put on notice of the likelihood of infringement and therefore, when it was on notice that its continuing to act could arise to willful infringement. The mere existence of the patents is not enough to demonstrate the notice of the patents necessary for proof of willful infringement to the extent the patents pertain to processes or methods and to the extent Sun/Oracle failed to mark the Java software as embodying the asserted patents. Nor is it likely that the occurrence of licensing discussions between Sun and Google is sufficient to show such notice unless, in the course of those discussions, Sun specifically identified the asserted patents as being related to their Java software.

Oracle's third motion seeks to exclude any evidence that Google may seek to introduce that, to the extent infringement has occurred, it was caused by modifications to the Android software by OEM's. Specifically, Oracle seeks to exclude any and all testimony or evidence that OEM's made such changes to Android. Oracle's argument is that Google testified in deposition and in interrogatory responses that it had no specific knowledge of such OEM modifications.

One problem with the Oracle argument in this instance is that it seeks to go beyond any testimony or evidence that Google may have had directly and seeks to exclude all evidence that may answer Oracle's original question - were OEMs making such modifications. Oracle had equal access to the third parties implementing Android in devices, and such third parties were clearly in a better position to answer Oracle's question than Google. Should Google be precluded from calling one of those third parties to testify as to modifications the OEM made to Android? Should Google be precluded from now introducing the software code from a third-party Android device to demonstrate that such modifications were made? It would appear that Oracle is overreaching with this motion when it attempts to exclude such evidence.

The fourth Oracle motion seeks to exclude certain testimony contained in the Astrachan report and/or otherwise offered by Google arising from past Sun statements or practices if those were (a) unrelated to the specific APIs at issue in the case or (b) personal opinion as to whether API specifications are or should be protected by copyright. This would not preclude Google from introducing other evidence as to the copyright protection (or lack thereof) of APIs. This motion would appear to be fairly straightforward and appropriate.

The final Oracle motion seeks to exclude "any evidence or argument contrary to the statements in Mr. Lindholm's August 6, 2010 email, concerning his investigation of alternatives to Java for Android, based on Google's refusal to permit discovery of the facts and circumstances of that investigation." This motion is over the top. Google has steadfastly argued that the Lindholm email (as finally sent and all auto-saved drafts) was privileged. It is Oracle, through the acts of its outside counsel, that has attempted to breach that privilege and then argue that the email was not privileged. Based on its claim of privilege, Google was well within its rights to refuse to permit discovery of the facts and circumstances of Lindholm's investigation; otherwise what is the point of the privilege?

Of course, if Judge Alsup, in ruling on the pending Google motion pertaining to the Lindholm email, upholds the magistrate's finding that the email was not, in fact, privileged then that changes the picture substantially. Oracle would then have the right to dig deeper into the background of what Mr. Lindholm did and what he discovered.

Skip to Comments

*************

Docket

498 - Filed and Effective: 10/07/2011

MOTION

Document Text: First MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence or

Argument Regarding Patent Reexaminations (MIL No. 1) filed by Oracle

America, Inc.. Motion Hearing set for 10/24/2011 02:00 PM in Courtroom

8, 19th Floor, San Francisco before Hon. William Alsup. Responses due by

10/21/2011. Replies due by 10/28/2011. (Attachments: # 1 Google

Opposition)(Muino, Daniel) (Filed on 10/7/2011) (Entered: 10/07/2011)

499 - Filed and Effective: 10/07/2011

MOTION

Document Text: Second MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence or

Argument That Google Relied on Legal Advice in Making Its Decisions to

Develop and Release Android (MIL No. 2) filed by Oracle America, Inc..

Motion Hearing set for 10/24/2011 02:00 PM in Courtroom 8, 19th Floor,

San Francisco before Hon. William Alsup. Responses due by 10/21/2011.

Replies due by 10/28/2011. (Attachments: # 1 Google Opposition)(Muino,

Daniel) (Filed on 10/7/2011) (Entered: 10/07/2011)

500 - Filed and Effective: 10/07/2011

MOTION

Document Text: Third MOTION in Limine to Preclude Google from

Offering Evidence or Argument That Third-Party OEMs Changed Infringing

Components of Android (MIL No. 3) filed by Oracle America, Inc.. Motion

Hearing set for 10/24/2011 02:00 PM in Courtroom 8, 19th Floor, San

Francisco before Hon. William Alsup. Responses due by 10/21/2011.

Replies due by 10/28/2011. (Attachments: # 1 Google Opposition)(Muino,

Daniel) (Filed on 10/7/2011) (Entered: 10/07/2011)

501 - Filed and Effective: 10/07/2011

MOTION

Document Text: Fourth MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence or

Argument Regarding Oracle's Past Actions With Application Programming

Interfaces (MIL No. 4) filed by Oracle America, Inc.. Motion Hearing set

for 10/24/2011 02:00 PM in Courtroom 8, 19th Floor, San Francisco before

Hon. William Alsup. Responses due by 10/21/2011. Replies due by

10/28/2011. (Attachments: # 1 Google Opposition)(Muino, Daniel) (Filed

on 10/7/2011) (Entered: 10/07/2011)

502 - Filed and Effective: 10/07/2011

MOTION

Document Text: Fifth MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence and

Argument Contrary to Statements in Tim Lindholm's August 6, 2010 Email

(MIL No. 5) filed by Oracle America, Inc.. Motion Hearing set for

10/24/2011 02:00 PM in Courtroom 8, 19th Floor, San Francisco before

Hon. William Alsup. Responses due by 10/21/2011. Replies due by

10/28/2011. (Attachments: # 1 Google Opposition)(Muino, Daniel) (Filed

on 10/7/2011) (Entered: 10/07/2011)

503 - Filed and Effective: 10/07/2011

Declaration

Document Text: Declaration of Daniel P. Muino in Support of 498

First MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence or Argument Regarding Patent

Reexaminations (MIL No. 1)First MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence or

Argument Regarding Patent Reexaminations (MIL No. 1), 500 Third MOTION

in Limine to Preclude Google from Offering Evidence or Argument That

Third-Party OEMs Changed Infringing Components of Android (MIL No.

3)Third MOTION in Limine to Preclude Google from Offering Evidence or

Argument That Third-Party OEMs Changed Infringing Components of Android

(MIL No. 3), 501 Fourth MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence or Argument

Regarding Oracle's Past Actions With Application Programming Interfaces

(MIL No. 4)Fourth MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence or Argument

Regarding Oracle's Past Actions With Application Programming Interfaces

(MIL No. 4), 502 Fifth MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence and Argument

Contrary to Statements in Tim Lindholm's August 6, 2010 Email (MIL No.

5)Fifth MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence and Argument Contrary to

Statements in Tim Lindholm's August 6, 2010 Email (MIL No. 5), 499

Second MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence or Argument That Google

Relied on Legal Advice in Making Its Decisions to Develop and Release

Android (MIL No. 2)Second MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence or

Argument That Google Relied on Legal Advice in Making Its Decisions to

Develop and Release Android (MIL No. 2) (Exhibits A through F) filed

byOracle America, Inc.. (Attachments: # 1 Exhibit A, # 2 Exhibit B, # 3

Exhibit C, # 4 Exhibit D, # 5 Exhibit E, # 6 Exhibit F)(Related

document(s) 498 , 500 , 501 , 502 , 499 ) (Muino, Daniel) (Filed on

10/7/2011) (Entered: 10/07/2011)

504 - Filed and Effective: 10/07/2011

EXHIBITS

Document Text: EXHIBITS re 503 Declaration in Support,

(Exhibits G through K) filed by Oracle America, Inc.. (Attachments: # 1

Exhibit H, # 2 Exhibit I, # 3 Exhibit J, # 4 Exhibit K)(Related

document(s) 503 ) (Muino, Daniel) (Filed on 10/7/2011) (Entered: 10/07/2011)

505 - Filed and Effective: 10/07/2011

EXHIBITS

Document Text: EXHIBITS re 503 Declaration in Support,

(Exhibits L through R) filed byOracle America, Inc.. (Attachments: # 1

Exhibit M, # 2 Exhibit N, # 3 Exhibit O, # 4 Exhibit P, # 5 Exhibit Q, #

6 Exhibit R)(Related document(s) 503 ) (Muino, Daniel) (Filed on

10/7/2011) (Entered: 10/07/2011)

506 - Filed and Effective: 10/07/2011

DECLARATION

Document Text: DECLARATION of Reid Mullen in Opposition to 498 First

MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence or Argument Regarding Patent

Reexaminations (MIL No. 1)First MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence or

Argument Regarding Patent Reexaminations (MIL No. 1), 500 Third MOTION

in Limine to Preclude Google from Offering Evidence or Argument That

Third-Party OEMs Changed Infringing Components of Android (MIL No.

3)Third MOTION in Limine to Preclude Google from Offering Evidence or

Argument That Third-Party OEMs Changed Infringing Components of Android

(MIL No. 3), 501 Fourth MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence or Argument

Regarding Oracle's Past Actions With Application Programming Interfaces

(MIL No. 4)Fourth MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence or Argument

Regarding Oracle's Past Actions With Application Programming Interfaces

(MIL No. 4), 502 Fifth MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence and Argument

Contrary to Statements in Tim Lindholm's August 6, 2010 Email (MIL No.

5)Fifth MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence and Argument Contrary to

Statements in Tim Lindholm's August 6, 2010 Email (MIL No. 5), 499

Second MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence or Argument That Google

Relied on Legal Advice in Making Its Decisions to Develop and Release

Android (MIL No. 2)Second MOTION in Limine to Exclude Evidence or

Argument That Google Relied on Legal Advice in Making Its Decisions to

Develop and Release Android (MIL No. 2) (Mullen Declaration in Support

of Google's Oppositions to Oracle's MILs 1-5) filed byOracle America,

Inc.. (Related document(s) 498 , 500 , 501 , 502 , 499 ) (Muino, Daniel)

(Filed on 10/7/2011) (Entered: 10/07/2011)

507 - Filed and Effective: 10/07/2011

Joint Administrative Motion

Document Text: Joint Administrative Motion to File Under Seal filed

by Oracle America, Inc.. (Attachments: # 1 Declaration of Daniel P.

Muino, # 2 Proposed Order Granting Plaintiff's Request to File Documents

Under Seal, # 3 Proposed Order Granting Defendant's Request to File

Documents Under Seal, # 4 Proposed Order Granting Motorola's Request to

File Documents Under Seal)(Muino, Daniel) (Filed on 10/7/2011) (Entered:

10/07/2011)

508 - Filed and Effective: 10/07/2011

Exhibit List

Document Text: Exhibit List Joint Trial Exhibit LIst by Oracle

America, Inc. (Muino, Daniel) (Filed on 10/7/2011) (Entered: 10/08/2011)

509 - Filed and Effective: 10/07/2011

DECLARATION

Document Text: DECLARATION of RUCHIKA AGRAWAL in Opposition to 496

MOTION in Limine No. 5, 494 MOTION in Limine No. 3, 492 MOTION in Limine

No. 1, 493 MOTION in Limine NO. 2, 495 MOTION in Limine No. 4 filed

byGoogle Inc.. (Attachments: # 1 Exhibit 1-1, # 2 Exhibit 1-2, # 3

Exhibit 1-3, # 4 Exhibit 1-4, # 5 Exhibit 1-5, # 6 Exhibit 1-6, # 7

Exhibit 1-7, # 8 Exhibit 1-8, # 9 Exhibit 1-9, # 10 Exhibit 1-10, # 11

Exhibit 1-11, # 12 Exhibit 1-12, # 13 Exhibit 2-1, # 14 Exhibit 2-2, #

15 Exhibit 2-3, # 16 Exhibit 2-4, # 17 Exhibit 2-5, # 18 Exhibit 2-6, #

19 Exhibit 2-7, # 20 Exhibit 2-8, # 21 Exhibit 2-9, # 22 Exhibit 2-10, #

23 Exhibit 2-11, # 24 Exhibit 2-12, # 25 Exhibit 2-13, # 26 Exhibit

2-14, # 27 Exhibit 2-15, # 28 Exhibit 2-16, # 29 Exhibit 2-17, # 30

Exhibit 3-1, # 31 Exhibit 3-2, # 32 Exhibit 3-3, # 33 Exhibit 3-4, # 34

Exhibit 3-5, # 35 Exhibit 3-6, # 36 Exhibit 3-7, # 37 Exhibit 3-8, # 38

Exhibit 3-9 [sealed], # 39 Exhibit 3-10 [sealed], # 40 Exhibit 3-11, # 41 Exhibit 4-1, #

42 Exhibit 4-2, # 43 Exhibit 4-3, # 44 Exhibit 5-1, # 45 Exhibit 5-2, #

46 Exhibit 5-3, # 47 Supplement 5-4)(Related document(s) 496 , 494 , 492

, 493 , 495 ) (Kamber, Matthias) (Filed on 10/7/2011) (Entered: 10/08/2011)

510 - Filed and Effective: 10/08/2011

Declaration

Document Text: Declaration of REID MULLEN in Support of 507 Joint

Administrative Motion to File Under Seal filed by Google Inc. (Related

document(s) 507 ) (Kamber, Matthias) (Filed on 10/8/2011) (Entered:

10/08/2011)

**************

Documents

498

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.

Plaintiff,

v.

GOOGLE INC.

Defendant.

Case No. CV 10-03561 WHA

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.’S

MOTION IN LIMINE NO. 1 TO

EXCLUDE EVIDENCE OR

ARGUMENT REGARDING

PATENT REEXAMINATIONS

Dept.: Courtroom 8, 19th Floor

Judge: Honorable William H. Alsup

Oracle moves the Court to preclude Google from introducing any evidence or argument

regarding the pending, non-final reexaminations of six of the patents-in-suit. The existence and

status of these non-final proceedings is irrelevant to the matters in this case. Any reference to

them at trial would be highly prejudicial and is likely to create juror confusion. Under Rule 403,

the Court should preclude Google from offering any evidence or argument regarding these nonfinal

patent reexaminations.

I. REEXAMINATIONS OF THE PATENTS-IN-SUIT

In early 2011, Google filed requests for reexamination of each of the patents-in-suit. In

March and April 2011, the PTO ordered reexaminations for all of the patents. The PTO

subsequently issued office actions for all but the ’104 patent.

For the ’520 patent, the claims that Oracle is asserting against Google in this case were all

confirmed patentable over the cited prior art. That proceeding is now concluded, except for the

issuance of the reexamination certificate. For the other six patents, the reexaminations are still

pending: (1) no office action has yet issued for the ’104 patent; (2) the ’447, ’476, and ’702 ex

parte reexaminations are awaiting further office actions from the PTO, following Oracle’s

responses filed in those actions; (3) the ’720 inter partes reexamination is awaiting a further

office action following responses from both Oracle and Google; and (4) the ’205 inter partes

reexamination is awaiting Oracle’s response to the PTO’s office action. The chart below

summarizes the current status of these reexaminations:

1

II. ARGUMENT

Federal courts have routinely relied on Federal Rule Evidence 403 to exclude evidence at

trial regarding co-pending, non-final reexaminations of the patents at issue, on the grounds that

such reexamination proceedings are not probative of patent invalidity and are highly likely to

confuse the jury. See, e.g., SRI Int’l Inc. v. Internet Sec. Sys., Inc., 647 F. Supp. 2d 323, 356 (D.

Del. 2009) (“Absent unusual circumstances . . . non-final decisions made during reexamination

are not binding, moreover, they are more prejudicial (considering the overwhelming possibility of

jury confusion) than probative of validity”); i4i Ltd. P’ship v. Microsoft Corp., 670 F. Supp. 2d

568, 583 (E.D. Tex. 2009) (”As explained elsewhere in this opinion, the simple fact that a

reexamination decision has been made by the PTO is not evidence probative of any element

regarding any claim of invalidity. . . . Even if it were, the evidence was substantially more

prejudicial than probative”); Amphenol T & M Antennas, Inc. v. Centurion Int’l, Inc., No. 00 C

4298, 2002 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 822, at *5 (N.D. Ill. 2002).

A non-final patent reexamination proceeding, of course, is not probative of invalidity or

unpatentability. Procter & Gamble Co. v. Kraft Foods Global, Inc., 549 F.3d 842, 848 (Fed. Cir.

2008) (“As this court has observed, a requestor’s burden to show that a reexamination order

should issue from the PTO is unrelated to a defendant’s burden to prove invalidity by clear and

2

convincing evidence at trial.”) (citation omitted); Hoechst Celanese Corp. v. BP Chems., Ltd., 78

F.3d 1575, 1584 (Fed. Cir. 1996) (“[T]he grant by the examiner of a request for reexamination is

not probative of unpatentability”); Volterra Semiconductor Corp. v. Primarion, Inc., No. C-08-

05129 JCS, 2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 49574, at *24 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 8, 2011) (“With respect to the

PTO Initial Office Actions and reexamination orders, … preliminary decisions and actions by the

PTO in the course of a reexamination proceeding are not probative of invalidity”). When office

actions and party responses are still pending, any interim rejections of patent claims are not

indicative of an ultimate finding of invalidity. Id.

Nor are the non-final reexaminations relevant to rebutting the charges of willful

infringement and intent to induce infringement. The initiation of a reexamination proceeding

does not exculpate an infringer from a finding of willfulness. Hoechst, 78 F.3d at 1583-84

(finding that the grant of a request for reexamination is not dispositive of willfulness). Moreover,

even if the reexaminations were relevant to willfulness and intent, the prejudicial effect of

disclosing them to the jury would vastly outweigh any probative value. See Presidio Components

Inc. v. Am. Tech. Ceramics Corp., No. 08-CV-335-IEG (NLS), 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 106795, at

*5 (S.D. Cal. Nov. 13, 2009) (“[E]ven if the reexamination proceedings are somehow relevant on

the issues of obviousness or willfulness, they are nevertheless unfairly prejudicial”) (citation

omitted); Declaration of Daniel P. Muino in Support of Oracle America, Inc.’s Motions In Limine

Nos. 1 Through 5 (“Muino Decl.”), Exhibit A, Realtime Data, LLC v. Packeteer, Inc., No. 6:08-

cv-144-LED-JDL, (E.D. Tex. Dec. 30, 2009), ECF No. 805 at 4 (“[A]lthough an ongoing

reexamination proceeding and the USPTO’s actions therein could be considered by the Court as a

factor in a willfulness determination at the summary judgment stage, during trial in a request for

judgments as a matter of law as to willful infringement, and/or post-verdict, it should not be

introduced before the jury due to the highly prejudicial effect the USPTO’s actions would have on

the jury”); Muino Decl. Exhibit B, Intel Corp. v. Commonwealth Scientific & Indus. Research

Org., No. 6:06-cv-551 (E.D. Tex. Apr. 9, 2009), ECF No. 518 at 4 (“[W]ithout any conclusions

of the PTO to rely upon, evidence that the PTO is currently reexamining the patent may work to

3

unduly alleviate Defendants’ ‘clear and convincing’ burden for both invalidity and willfulness in

front of the jury”).

B. Reference To The Non-Final Reexaminations At Trial Would Be

Highly Prejudicial And Likely To Confuse The Jury

Any reference to the non-final reexaminations in front of the jury would be prejudicial to

Oracle, as it would create a high likelihood of confusing and misleading the jury regarding the

validity of the patents. See Boston Scientific Corp. v. Cordis Corp., No. 10-315-SLR, 2011 U.S.

Dist. LEXIS 46210, at *1-2 (D. Del. Apr. 28, 2011) (“It is generally not the court’s practice to

admit the reexamination record as trial evidence. Rejections on reexamination are not binding,

and such evidence is almost always more prejudicial than probative.”). Oracle’s patents are

entitled to a presumption of validity and may only be invalidated based on clear and convincing

evidence. See Microsoft Corp. v. i4i Ltd. P’ship, 131 S. Ct. 2238 (2011) (applying the clear and

convincing standard to all prior art references regardless of their use in initial examination); z4

Techs., Inc. v. Microsoft Corp., 507 F.3d 1340, 1354 (Fed. Cir. 2007) (invalidity must be shown

by clear and convincing evidence). The jury will be instructed on this standard. Informing the

jury that the PTO is reexamining the patents may cause jurors to erroneously conclude that the

patents are invalid or no longer entitled to a presumption of validity. See Amphenol, 2002 U.S.

Dist. LEXIS 822, at *5 (“[T]elling the jury that the patent has been called into question by the

Patent Office may significantly influence the jury’s application of the presumption of validity and

significantly prejudice [the patentee]. The prejudicial potential of this evidence far outweighs any

probative value it may have.”). Jurors may well mistake the PTO’s interim rejections of certain

patent claims as indicative of the government’s final position on the validity of those claims.

Moreover, if the jury were informed of the non-final reexaminations, the parties and the

Court would be obliged to explain the PTO’s reexamination procedures to the jury so as to

mitigate confusion. This may lead to disputes on how to characterize the reexamination process

and how to explain the substantive positions taken by the parties and the PTO in the

reexaminations. Such disruption will be avoided if references to the non-final reexaminations are

precluded.

4

In an analogous situation, this Court excluded argument regarding the prosecution

histories of certain trademark applications, including non-final Office Actions, in Autodesk, Inc.

v. Dassault Systémes Solidworks Corp., No. 3:08-cv-04397-WHA (N.D. Cal. Dec. 23, 2009),

ECF No. 209. (Muino Decl. Exhibit C.) In that case, Autodesk moved in limine to exclude

evidence or argument regarding these materials on the grounds that their introduction would be

prejudicial and likely to confuse the jury. (Id.) The Court precluded mention of the non-final

office actions and other prosecution filings during opening statements. (Muino Decl. Exhibit D,

Autodesk, ECF No. 240 at 52-53 (Dec. 31, 2009).)

III. CONCLUSION

The non-final reexaminations are not probative of invalidity or any other issues of

relevance to this case. Permitting their introduction creates a high risk of confusing and

misleading the jury. Pursuant to Federal Rule Evidence 403, Oracle requests that the Court

preclude Google from offering any argument or evidence at trial regarding the six non-final

reexaminations of the patents-in-suit.

Dated: September 24, 2011

MICHAEL A. JACOBS

MARC DAVID PETERS

DANIEL P. MUINO

MORRISON & FOERSTER LLP

By: /s/ Daniel P. Muino

Attorneys for Plaintiff

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.

5

499

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.

Plaintiff,

v.

GOOGLE INC.

Defendant.

Case No. CV 10-03561 WHA

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.’S

MOTION IN LIMINE NO. 2 TO

EXCLUDE EVIDENCE OR

ARGUMENT THAT GOOGLE

RELIED ON LEGAL ADVICE IN

MAKING ITS DECISIONS TO

DEVELOP AND RELEASE

ANDROID

Dept.: Courtroom 8, 19th Floor

Judge: Honorable William H. Alsup

Oracle moves the Court to preclude Google from introducing any evidence or argument

that Google relied on advice of counsel in connection with its decisions to develop and release

Android. Google did not make the required disclosures under Patent L.R. 3-7 of documents

reflecting any legal advice upon which it intends to rely. That alone should preclude Google from

relying on advice of counsel to rebut allegations of willful patent infringement or intent to induce

infringement. Moreover, during discovery, Google routinely asserted privilege to prevent Oracle

from obtaining discovery on any legal advice Google may have received, with respect to both

patent and copyright issues. Accordingly, Google should also be precluded from invoking legal

advice as a defense to willful copyright infringement. For these reasons, the Court should

exclude any evidence or argument that Google relied on legal advice in deciding to develop and

release Android.

I. GOOGLE’S ASSERTION OF PRIVILEGE OVER LEGAL ADVICE

Google has invoked the attorney-client privilege to block all of Oracle’s discovery into

any legal advice Google received in connection with Android. First, Google did not produce any

documents relating to advice of counsel under Patent Local Rule 3-7. That rule requires “each

party relying upon advice of counsel as part of a patent-related claim or defense” to produce a

copy of “any written advice” and provide “a written summary of any oral advice” on which the

party intends to rely and for which it has waived the attorney-client privilege and work product

protection. Patent L.R. 3-7. Failure to comply with the rule means that the party may not rely on

advice of counsel as a defense.

Second, Google asserted privilege and withheld from production numerous documents

purportedly reflecting legal advice related to Android. Google’s privilege log contains many

entries identifying privileged legal opinions that have been withheld from Oracle. (Declaration of

Daniel P. Muino in Support of Oracle America, Inc.’s Motions In Limine Nos. 1 Through 5

(“Muino Decl.”), ¶ 5.) Indeed, Google systematically asserted privilege over any

communications regarding advice of Google’s counsel.

Third, Google instructed its witnesses not to answer questions regarding legal advice

pertaining to Android, based on the attorney-client privilege. For example, counsel instructed

1

Andy Rubin, Google’s Senior Vice President of Mobile and co-founder of Android, not to answer

questions regarding legal advice pertaining to executive decisions on Android’s release [REDACTED] Google’s assertion of privilege prevented Oracle

from discovering the nature of any legal advice about this topic:

Q. BY MR. JACOBS: Have you interacted with the legal team over issues

associated with the release of Android that prevented it from giving you the legal

bit?

MS. ANDERSON: Objection. Instruct the witness not to answer on grounds of

privilege as phrased.

Q. BY MR. JACOBS: Has the legal team ever conveyed to you we have concerns

about a -- an Android release and we can't give you the legal bit?

MS. ANDERSON: Objection. Instruct the witness not to answer on the grounds

of attorney-client privilege as phrased.

MR. JACOBS: And for all those instructions, you're following your counsel's

instructions not to answer the question?

THE WITNESS: Yes, I am.

(Muino Decl. Exhibit E at 25:13-26:2 (July 27, 2011 Deposition Transcript of

Andrew Rubin).)

Google also asserted privilege over legal advice that Mr. Rubin received after this lawsuit was

filed:

Q. BY MR. JACOBS: So let me ask you this question with the intent of dividing

up possible privileged communications from non-privileged activities you may

have conducted. Have you actually reviewed what I'll refer to as the infringement

2

contentions in this lawsuit? It's a very thick document in which Oracle sets forth

the claims of the patents-in-suit and the accused functionality.

MS. ANDERSON: Objection. Instruct the witness not to answer on the grounds

of attorney-client privilege to the extent responding would inherently disclose

communications you had with counsel.

THE WITNESS: I'll take the instruction of my counsel.

Q. BY MR. JACOBS: Do you have a view, based on a review of the patents in

the litigation, whether Android is bringing any of those patents?

MS. ANDERSON: Objection. Form. And also object to the extent the question is

seeking to disclose communications with counsel, on that basis, I would instruct

you not to answer on grounds of privilege, otherwise you may answer.

THE WITNESS: I will not answer based on the advice of my counsel.

Q. BY MR. JACOBS: Have you asked anybody on your team to assist counsel in

reviewing the allegations?

MS. ANDERSON: Objection. Instruct the witness not to answer on grounds of

attorney-client privilege.

THE WITNESS: I'll take that advice.

Q. BY MR. JACOBS: Has anybody on your team assisted counsel in reviewing

Oracle's patent infringement allegations?

MS. ANDERSON: Objection, and instruct the witness not to answer on the

grounds of attorney-client privilege.

THE WITNESS: Again, I'll take that advice.

(Id. at 36:14-37:25.)

...

Q. BY MR. JACOBS: Did you get -- did you involve Google's counsel in review

of the terms of click-through licenses at any point in the development of Android?

MS. ANDERSON: Objection. Instruct the witness not to answer on grounds of

attorney-client privilege.

THE WITNESS: I'll take that advice, thank you.

(Id. at 109:12-20.)

3

Google also used privilege as a shield to prevent Oracle from discovering any legal advice

received by Google regarding the copyrightability of APIs:

Q. And in particular, I just have to ask this again: Did you consult with counsel

over your tenure at Google around the question of whether API's were

copyrightable as it related to Android?

MS. ANDERSON: Objection. Instruct the witness not to answer on the grounds

of attorney-client privilege.

THE WITNESS: I'll accept the advice of my attorney.

(Id. at 155:22-156:5.)

Google asserted privilege and instructed Daniel Bornstein, Google engineer and one of the

lead developers for Android, not to answer questions regarding whether or not he received advice

of counsel about what materials he could look at to develop Android. (Muino Decl. Exhibit F at

161:22-162:21 (May 16, 2011 Deposition Transcript of Daniel Bornstein).) Google’s instruction

prevented discovery on this subject:

Q. At the time, referring to, say, in early 2007, what was the source of your

understanding that it was that you could use documentation to gain understanding

of the idea of an API?

A. I don't know specifically.

Q. At the time, did you have -- receive any advice of counsel about what

materials you could or could not look at to develop Android?

A. So I have had discussions with lawyers on and off throughout my career. I

don't know how much I can say about the content of those.

MR. BABER: Instruct the witness to not say anything about the content of

discussions.

THE WITNESS: Okay.

BY DR. PETERS:

Q. Did you see the -- were you ever advised by counsel that it was permissible to

use a Javadoc to develop Android?

MR. BABER: Object and instruct the witness not to answer the question on the

grounds of privilege.

BY DR. PETERS:

Q. Will you follow your counsel's instructions?

A. I will follow my counsel's instructions.

(Id.)

Further, Google asserted privilege in the deposition of Bob Lee, former Google engineer

in charge of developing Android’s class libraries, and instructed him not to answer questions

regarding whether Google analyzed the implications of Sun’s license dispute with Apache on the

4

release of Android. (Muino Decl. Exhibit G at 73:4-12 (August 3, 2011 Deposition Transcript of

Bob Lee).) Google’s instruction prevented discovery on this subject:

Q. BY MR. PETERS: Did Google analyze whether or not the dispute between

Sun and Apache was any bar to its release of Android?

MR. PURCELL: Object to the form.

And to the extent you're aware of any analysis done by Google's lawyers or at the

instruction of Google's lawyers, I instruct you not to answer.

THE WITNESS: Okay. I'm not sure. I don't know.

(Id.)

Fourth, Google asserted privilege in many of its responses to Oracle’s interrogatories. For

example, Google asserted privilege in its response to Interrogatory No. 2. (Muino Decl. Exhibit

H at 7-8 (Google’s Response to Oracle’s 1st Set of Interrogatories dated January 6, 2011).)

Oracle’s Interrogatory No. 2 asks Google to “[i]dentify who at Google was and is responsible for

Android’s compliance with the intellectual property rights of third parties and briefly describe

their roles in that regard.” (Id.) Google asserted “attorney-client privilege, the work product

doctrine, and/or any other applicable privilege, immunity, or protection.” (Id.) Further, it appears

that Google failed to identify anyone from the legal team, nor did Google describe “their roles” in

ensuring Android’s compliance. Google’s assertion of privilege over any legal advice it received

pertaining to Android has been consistent and complete.

II. GOOGLE SHOULD BE PRECLUDED FROM INVOKING ADVICE OF

COUNSEL AS A DEFENSE

Having failed to disclose the basis of any advice of counsel defense and having blocked

all discovery on this subject, Google should be precluded from arguing that it relied on legal

advice in connection with its decisions to develop and release Android.

First, Patent L.R. 3-7 is perfectly clear that advice of counsel defenses are precluded if a

party fails to waive privilege and produce documents underlying the defense:

[E]ach party relying upon advice of counsel as part of a patent-related claim or

defense for any reason shall:

5

(a) Produce or make available for inspection and copying any written advice and

documents related thereto for which the attorney-client and work product

protection have been waived;

(b) Provide a written summary of any oral advice and produce or make available

for inspection and copying that summary and documents related thereto for which

the attorney-client and work product protection have been waived; . . . .

A party who does not comply with the requirements of this Patent L.R. 3-7 shall

not be permitted to rely on advice of counsel for any purpose absent a stipulation

of all parties or by order of the Court.

Patent L.R. 3-7. The rule is absolute – unless underlying documents and oral advice are

disclosed, invoking advice of counsel to rebut any patent-related claim (including willfulness and

intent to induce infringement) is precluded, absent a stipulation or leave of Court. Protective

Optics, Inc. v. Panoptx, Inc., 488 F. Supp. 2d 922, 923 (N.D. Cal. 2007) (“a defendant who

wishes to escape charges of willful infringement may rely on the advice of his attorney, but he

must alert the other side of his intention to do so, and he must turn over (or identify in a privilege

log) all documents that relate to the attorney’s opinion. Failure to do so precludes use of the

attorney’s opinion as a defense.”) Google has not made the required disclosures under L.R. 3-7;

accordingly, it is precluded from offering an advice of counsel defense as a rebuttal to Oracle’s

allegations of willful patent infringement and intent to induce infringement.

Second, Ninth Circuit law is clear that legal advice as a defense to willful copyright

infringement must also be excluded if the party has invoked the attorney-client privilege to block

discovery on that advice. See Columbia Pictures Indus., Inc. v. Krypton Broad. of Birmingham,

Inc., 259 F.3d 1186, 1196 (9th Cir. 2001) (affirming exclusion of legal advice as a defense to

willful copyright infringement, because defendant invoked privilege to block discovery on that

advice); accord Chevron Corp. v. Pennzoil Co., 974 F.2d 1156, 1162 (9th Cir. 1992) (privilege

cannot be waived selectively and thus used as a sword and shield); SNK Corp. of Am. v. Atlus

Dream Ent’t Co., 188 F.R.D. 566, 571 (N.D. Cal. 1999) (“[f]airness dictates that a party may not

use the attorney-client privilege as both a sword and a shield”).

In Columbia Pictures, the Ninth Circuit affirmed a trial court’s decision to exclude

evidence of defendant’s reliance on advice of counsel, because the defendant asserted privilege

6

over the same evidence during discovery. Columbia, 259 F.3d at 1196. Defendant in that case

sought to present evidence regarding advice of counsel to rebut an allegation of willful copyright

infringement. Id. However, defendant “refused to answer questions regarding his interactions

with counsel at his deposition.” Id. The district court granted plaintiff’s motion in limine to

exclude evidence relating to defendant’s advice of counsel. Id. Defendant offered “to make

himself available for deposition” on the subject of advice of counsel, but the district court rejected

this offer, stating that “[t]he Defendant cannot now, at the eleventh hour, make himself available

for a deposition.” Id. (quoting district court). The Ninth Circuit agreed that “refusing to answer

questions regarding relevant communications with counsel until the ‘eleventh hour’” was

sufficient ground for precluding testimony regarding the advice of counsel. Id.

Here, Google has used privilege as a shield. Google has systematically asserted attorneyclient

privilege on all subjects relating to advice of counsel, whether pertaining to patents or

copyrights. Google routinely asserted privilege at depositions of its witnesses on subjects

regarding advice of counsel, including conversations surrounding the legal team’s analysis and

checking of a “legal bit” to approve an Android release, as well as post-complaint analysis of

Oracle’s claims of infringement.

For these reasons, any evidence or argument that Google relied on legal advice in

connection with its Android decisions should be excluded from trial. Google should be precluded

from presenting evidence or argument on both the substance of Google’s advice of counsel, as

well as the fact that Google obtained and relied on that advice.

III. CONCLUSION

Google used the attorney-client privilege to shield from discovery any evidence regarding

legal advice it received in connection with its Android decisions. Under Patent L.R. 3-7 and

Ninth Circuit law, Google is precluded from asserting any advice of counsel defense. Oracle

requests that the Court exclude any evidence or argument that Google relied upon legal advice in

making its decisions to develop and release Android.

7

Dated: September 24, 2011

MICHAEL A. JACOBS

MARC DAVID PETERS

DANIEL P. MUINO

MORRISON & FOERSTER LLP

By: /s/ Daniel P. Muino

Attorneys for Plaintiff

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.

8

500

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.

Plaintiff,

v.

GOOGLE INC.

Defendant.

Case No. CV 10-03561 WHA

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.’S

MOTION IN LIMINE NO. 3 TO

PRECLUDE GOOGLE FROM

OFFERING EVIDENCE OR

ARGUMENT THAT THIRD-PARTY

OEMS CHANGED INFRINGING

COMPONENTS OF ANDROID

Dept.: Courtroom 8, 19th Floor

Judge: Honorable William H. Alsup

Oracle moves the Court to preclude Google from offering argument or evidence at trial

that any changes were made to the infringing components of the Android source code by third

party original equipment manufacturers (OEMs). Throughout this litigation, Google has

steadfastly denied knowledge of any modifications made by OEMs to the infringing components

of Android: (1) In response to Oracle’s Interrogatory 21, Google stated that it had “no direct,

specific knowledge with regard to how third parties modify the accused Android source code and

documentation”; and (2) Google’s corporate designee, Patrick Brady, testified that he did not

know for certain, one way or the other, whether OEMs had changed the infringing components of

Android installed on Android devices. Having disclaimed any knowledge of OEM changes to the

infringing components, Google should be barred from offering any evidence or argument on that

subject at trial.

I. GOOGLE HAS DENIED KNOWLEDGE OF OEM CHANGES TO THE

INFRINGING COMPONENTS OF ANDROID

Oracle accuses the Android platform of infringing the patents-in-suit through several key

platform components: (1) the Dalvik virtual machine, (2) the dexopt component, (3) the zygote

process, (4) the dx tool, and (5) Android’s java.security framework (collectively, the “infringing

components”). Through an interrogatory (No. 21) and a Rule 30(b)(6) deposition topic (No. 7),

Oracle sought discovery from Google regarding its knowledge of any modifications made by

third parties to the infringing components of Android. In its interrogatory answer and through the

testimony of its corporate designee, Google flatly denied any specific knowledge of whether or

not OEMs modify the infringing components of Android to be installed on their Android devices.

Instead, Google insisted that OEMs “may freely modify Android source code subject to the terms

of [the Apache License],” presumably without Google’s knowledge or oversight.

Google’s Response to Oracle’s Interrogatory 21: Oracle’s Interrogatory 21 asked Google

to “[i]dentify and describe in detail each modification made by third parties to the allegedly

infringing portions of Android source code and documentation identified by Oracle’s copyright

and patent infringement contentions, including the author of, date of, and basis for each such

modification.” (Declaration of Daniel P. Muino in Support of Oracle America, Inc.’s Motions In

1

Limine Nos. 1 Through 5 (“Muino Decl.”), Exhibit I, Defendant Google, Inc.’s Responses to

Plaintiff’s Interrogatories, Set Four, at 10.) On July 29, 2011, Google responded as follows:

Subject to the foregoing objections and the General Objections,

without waiver or limitation thereof, Google states that it has no

direct, specific knowledge with regard to how third parties modify

the accused Android source code and documentation. Google

releases Android source code to the public under the open source

Apache License, Version 2.0. Any third party may freely modify

Android source code subject to the terms of this license.

Id. at 11 (Google’s objections omitted). To date, Google has not supplemented this response.

Testimony of Google’s Corporate Designee, Patrick Brady: Topic 7 of Oracle’s Rule

30(b)(6) deposition notice to Google sought testimony regarding “[m]odifications made by third

parties to the allegedly-infringing portions of Android identified by Oracle’s copyright and patent

infringement contentions, including the author of, date of, and basis for each such modification.”

(Muino Decl. Exhibit J, Plaintiff’s Notice of Deposition of Defendant Google Inc. Pursuant to

Fed. R. Civ. P. 30(b)(6), Topics 4-9.)

On July 21, 2011, Oracle took the deposition of Google’s corporate designee on Topic 7,

Patrick Brady, Director of Android Partner Engineering. [REDACTED]

2

[REDACTED] But Mr. Brady

could not say for certain that changes had been made to the Dalvik virtual machine in that device,

and had no knowledge of the specifics of any such changes.

II. GOOGLE SHOULD BE PRECLUDED FROM OFFERING EVIDENCE OR

ARGUMENT ON OEM CHANGES TO INFRINGING ANDROID COMPONENTS

This Court has previously ruled that, with respect to evidence admissible at trial, parties

“will be held to their discovery answers.” Doe v. Reddy, No. C 02-05570 WHA, 2004 U.S. Dist.

LEXIS 30792, *14-15 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 24, 2004) (Alsup, J.). In Doe v. Reddy, the Court granted

a motion in limine precluding defendant (accused of sexual relations with an underage girl) from

suggesting at trial that plaintiffs (the girl’s parents) knew about the sexual relations. Id. The

Court noted that defendant’s interrogatory responses had identified no evidence regarding

parental knowledge of the sexual relations. Id. While the response did refer to certain deposition

testimony, that testimony did not establish parental knowledge. Id. Accordingly, the Court ruled

that “Defendants will be held to their discovery answers” and “at trial no suggestion will be made

that the parents knew of the sexual relations.” Id.

Other courts in the 9th Circuit have followed this principle, limiting evidence admissible

at trial to what is disclosed in discovery. See Service Employees Int’l Union (“SEIU”) v. Roselli,

No. C 09-00404 WHA, 2010 WL 963707, at *5 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 16, 2010) (granting motion in

limine to exclude evidence based on defendant’s refusal to provide discovery on that evidence);

Tech. Licensing Corp. v. Thomson, Inc., No. CIV. S-03-1329, 2005 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 24239, at

*16-17 (E.D. Cal. June 30, 2005) (limiting evidence at trial to information disclosed in response

to interrogatory). In the SEIU case, this Court granted a motion in limine to exclude evidence

regarding certain activities aimed at obtaining workers’ signatures, on the grounds that defendants

3

refused to answer questions about those activities during discovery. SEIU, 2010 WL 963707, at

*5. The Court observed, “having avoided disclosing in discovery the materials sought by

plaintiffs regarding defendants’ post-trusteeship activities on grounds of relevancy, it would be

unfair sandbagging to allow defendants to now assert those same materials as a defense to

plaintiffs’ claims.” Id.

In this case, Google’s interrogatory response disclaimed any specific knowledge of OEM

modifications of Android code. Although Google’s response was served after the deposition of

Mr. Brady on Topic 7, Google did not incorporate Mr. Brady’s testimony into its response. So

Google has disclosed nothing at all in response to Oracle’s interrogatory regarding OEM changes

to Android. Accordingly, Google should be precluded from suggesting at trial that OEMs

changed the infringing components of Android, since it disclosed no evidence on this subject in

its interrogatory response. Doe v. Reddy, 2004 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 30792, at *14.

Furthermore, even if Mr. Brady’s testimony were counted as disclosure on this subject, he

too disclaimed specific knowledge of OEM modifications to the infringing components of

Android. [REDACTED] Mr. Brady’s testimony provides no basis for Google to argue that OEMs made changes to

the infringing components of Android.

The preclusion of argument and evidence regarding OEM changes to Android should

extend to Google’s experts, who should not be permitted to speculate regarding modifications to

the Android code without a factual basis. For instance, Google’s expert, David August, stated in

his report that “device manufacturers often modify the source code.” (Muino Decl. Exhibit L

¶ 108 (Expert Report of David I. August, Ph.D. Regarding the Non-Infringement of U.S. Patent

No. 6,910,205).) Yet, Mr. August offered no basis for this statement other than an excerpt from

4

the deposition of Mr. Brady.1 (Id. Ex. M at 131:2-9.) While Mr. Brady did testify regarding

certain OEM changes to the Android code in general, he disclaimed any specific knowledge of

OEM changes to the infringing components of Android. Accordingly, Mr. Brady’s testimony

provides no basis on which Mr. August, or any other Google expert, may opine on purported

OEM changes to the Android code.

III. CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, Oracle requests that the Court preclude Google, its attorneys,

witnesses, and experts, from offering any argument or evidence at trial that OEMs made changes

to the infringing components of the Android code installed on their devices.

Dated: September 24, 2011

MICHAEL A. JACOBS

MARC DAVID PETERS

DANIEL P. MUINO

MORRISON & FOERSTER LLP

By: /s/ Daniel P. Muino

Attorneys for Plaintiff

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.

_________________________

1 Mr. August acknowledged that he has not examined any third party devices, nor has he

conducted any research into how third party manufacturers might modify the source code.

(Muino Decl. Exhibit M at 128:10-129:4, 130:10-19 (September 16, 2011 Deposition of David I.

August).)

5

501

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.

Plaintiff,

v.

GOOGLE INC.

Defendant.

Case No. CV 10-03561 WHA

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.’S

MOTION IN LIMINE NO. 4 TO

EXCLUDE EVIDENCE OR

ARGUMENT REGARDING

ORACLE’S PAST ACTIONS WITH

APPLICATION PROGRAMMING

INTERFACES

Dept.: Courtroom 8, 19th Floor

Judge: Honorable William H. Alsup

Oracle moves the Court to exclude any evidence or argument regarding Oracle’s and

Sun’s alleged use of third party application programming interfaces (“APIs”) and past statements

regarding copyright protection for interfaces generally. Google proffered examples of such

evidence in the opening report of its copyright expert Owen Astrachan and in support of its

motion for summary judgment on copyright. (See, e.g., ECF. No. 262-1, Declaration of Owen in

Support of Defendant Google Inc.’s Motion for Summary Judgment (“Astrachan Decl.”), Ex. 1

¶¶ 62-86 and Ex. C (alleging that Oracle and Sun implemented APIs from third parties’ preexisting

software); ECF. No. 263-7 Declaration of Michael S. Kwun in Support of Defendant

Google Inc.’s Motion for Summary Judgment (“Kwun Decl.”), Ex. G (September 1994 testimony

of former Sun CTO and current Google Chairman Eric Schmidt regarding open interfaces to the

National and Global Information Infrastructure).) As described below, additional examples can

be found in Google’s discovery requests.

None of this evidence is relevant. It is not specific to the Java-related inventions and

copyrighted works at issue in this case, and it is irrelevant to the issue of whether they are

copyrightable in any event. Moreover, the risks of jury confusion, unfair prejudice, and waste of

time substantially outweigh any minimal relevance the evidence may have.

I. ARGUMENT

“Evidence which is not relevant is not admissible.” Fed. R. Evid. 402. “Although

relevant, evidence may be excluded if its probative value is substantially outweighed by the

danger of unfair prejudice, confusion of the issues, or misleading the jury, or by considerations of

undue delay, waste of time, or needless presentation of cumulative evidence.” Fed. R. Evid. 403.

“‘Unfair prejudice’ within [this] context means an undue tendency to suggest decision on an

improper basis.” Dream Games of Ariz., Inc. v. PC Onsite, 561 F.3d 983, 993 (9th Cir. 2009)

(quoting Fed. R. Evid. 403 Advisory Committee’s note).

1

A. Google’s Evidence About APIs Is Not Relevant.

1. Sun’s and Oracle’s Alleged Use of Third Party APIs Is Not

Relevant.

In his opening report, Dr. Astrachan alleges that Oracle’s predecessor Sun implemented

portions of APIs from a long defunct spreadsheet program called Visicalc dating from 1979, that

Sun implemented portions of APIs from Linux as part of the Solaris operating system, and that

Oracle implemented portions of APIs from IBM (allegedly a handful of names), again dating

from 1979, in its database software. (See ECF. No. 262-1, Astrachan Decl. ¶¶ 62-86 and Ex. C.)

This case concerns whether Google unlawfully appropriated copyrightable expression and

patented inventions from Oracle’s Java platform. Evidence of Sun’s and Oracle’s alleged use of

portions of third party APIs in non-Java products is irrelevant.

The Court’s recent order on the copyright claims in this case highlights the need to

analyze specific elements of the works at issue when determining copyrightability. “If Google

believes, for example, that a particular method declaration is a scene a faire or is the only possible

way to express a given function, then Google should provide evidence and argument supporting

its views as to that method declaration.” (ECF. No. 433 at 9.) The evidence Google seeks to

offer is not only unrelated to specific elements of the Java API specifications, but it is completely

unrelated to Java.

Dr. Astrachan’s testimony is particularly irrelevant here because it does not establish that

the circumstances relating to Sun’s and Oracle’s alleged use of third party APIs are similar to the

facts at issue here. Dr. Astrachan does not even attempt in his report to compare the nature and

extent of what Oracle allegedly used from third parties to what Google copied from the Java

platform. To the contrary, Dr. Astrachan admits that he did not research whether Oracle’s

spreadsheet products allegedly used anything more than a set of names from third parties:

[REDACTED]

2

[REDACTED]

As detailed in Oracle's opposition to Google's copyright summary judgment motion (ECF. No. 396, Oracle America, Inc.'s Opposition to Google's Motion for Summary Judgment on Count VIII of Oracle's Amended Complaint), Google misappropriated not only an entire collection and arrangement of names, but other elements such as method signatures, the selection and arrangement of the elements, their complex interdependencies, and the prose text that describes them. Oracle's alleged use of certain names in a spreadsheet program, and nothing more, is not relevant to determining copyrightability of the Java platform, or whether Google's wholesale copying of the Java APIs constitutes "fair use."

In addition, Dr. Astrachan admitted that he did not research whether Oracle or Sun had permission to use the third party APIs he cites:

[REDACTED]

[REDACTED] In

In summary. Dr. Astrachan's spreadsheet example involves a product from the 1970s (ECF. No. 262-1, Astrachan Decl. ¶ 65), from a company that no longer exists, and as far as Dr. Astrachan knows, the company may have permitted Oracle's particular alleged use.

________________________

[FOOTNOTE REDACTED]

3

Dr. Astrachan’s testimony on Oracle’s alleged use of third party APIs is wholly irrelevant

to the central issue here—whether Google infringed Oracle’s Java copyrights—and it should

therefore be excluded under Rule 402.

2. Former Sun or Oracle Employee Statements About

Copyrightability of APIs Are Not Relevant.

Google’s evidence of statements made by former Sun employees is similarly irrelevant.

Google’s copyright summary judgment motion repeatedly cites statements made in 1994

congressional testimony by then-Sun CTO and current Google chairman Eric Schmidt relating to

the copyrightability of APIs. (ECF. No. 260, Defendant Google Inc.’s Notice of Motion and

Motion for Summary Judgment on Count VIII of Plaintiff Oracle America’s Amended Complaint

(“Google’s MSJ”), at 1; ECF. No. 263-7, Kwun Decl. Ex. G.) The prominence Google intends to

give to these statements at trial, and the purpose for which it intends to use them, is evident from

the fact that Dr. Schmidt is quoted in the very first paragraph of Google’s brief, stating his belief

that “interface specifications are not protectable under copyright.” (Id.) Dr. Schmidt is quoted

two more times in Google’s brief to similar effect. (ECF. No. 260, Google’s MSJ at 2, 25).

Google’s Requests for Admission (an excerpt of which are filed herewith as Muino Decl.

Exhibit O (“Requests”)) contain additional statements regarding the copyrightability of non-Java

products that Google tries to attribute to former Sun or Oracle employees. (See, e.g., Requests

349-54 (quoting alleged policies of the American Committee for Interoperable Systems

(“ACIS”), of which Google claims Sun was a member).) For example, Request 350 asks Oracle

to “Admit that, as an American Committee for Interoperable Systems member, Sun supported the

following principle: ‘The rules or specifications according to which data must be organized in

order to communicate with another program or computer, i.e., interfaces and access protocols, are

not protectable expression under copyright law.’” (See also Requests 355-79 (referencing and

quoting amicus briefs allegedly written by former Sun employees on behalf of ACIS in Sony

Computer Entm’t v. Connectix Corp., 203 F.3d 596 (9th Cir. 2000)); Lotus Dev. Corp. v. Borland

Int’l, Inc., 515 U.S. 1191 (1995); Bateman v. Mnemonics, Inc., 79 F.3d 1532 (11th Cir. 1996);

Computer Assocs. Int’l., Inc. v. Altai, Inc., 982 F.2d 693 (2d Cir. 1992); and DVD Copy Control

4

Ass’n Inc. v. Brunner, 10 Cal. Rptr. 3d 185 (Cal. Ct. App. 6th Dist. 2004).) Dr. Schmidt’s 1994

testimony is referenced in Requests 380-81.

These statements are completely irrelevant and should be excluded under Rule 402. Dr.

Schmidt’s 1994 testimony, for example, which came before the first Java Development Kit was

even published, was part of a discussion on interfaces relating to the planned National

Information Infrastructure—not Java specifically. (ECF. No. 263-7, Kwun Decl. Ex. G.) Nor

was Java at issue in the cases for which ACIS submitted amicus briefs. But even if the statements

had been intended to encompass Java, they would not be relevant here. Statements advocating

what the law should be, made over 10 years ago, have no place in this trial. The question of

whether APIs, as a matter of policy, should not be copyrightable is initially one for the legislature.

Indeed, Dr. Schmidt was testifying before Congress. And if Google is trying to admit former Sun

or Oracle employees’ statements on the issue of whether APIs generally are copyrightable, that is

a question of law for the Court, not the jury.

B. The Risk of Jury Confusion, Unfair Prejudice, and Undue Delay

Substantially Outweighs any Probative Value.

Even if the Court finds that Oracle’s prior statements and alleged use of non-Java APIs are

somehow relevant to Google’s defenses, this evidence should still be excluded under Fed. R.

Evid. 403 because any minimal relevance they would have are outweighed by prejudice, undue

delay, and the risk of jury confusion.

Google offers Dr. Astrachan’s third party API examples to suggest that Oracle, like

Google, has copied other companies’ APIs and therefore is an unworthy plaintiff. Oracle,

however, is not being sued for infringement. As discussed above, Google’s expert did not

investigate the circumstances or the extent of the material Oracle allegedly used from others or

how that relates to Google’s copying in this case. Based on an incomplete record, a jury might

try to punish Oracle for innocuous acts that have no relevance to this case. Courts routinely

exclude allegations of purportedly bad acts by a plaintiff under Rule 403. See, e.g., Leegin

Creative Leather Prods. v. Belts by Nadim, Inc., 316 Fed. Appx. 573, 575 (9th Cir. 2009) (finding

5

no abuse of discretion “in holding evidence of Leegin’s alleged infringement of other copyrights

not at issue in the trial inadmissible under Rules 401 and 403”).

Allowing this evidence would also complicate the trial and cause undue delay, in violation

of Rule 403. See Hodge v. Mayer Unified Sch. Dist. No. 43 Governing Bd., No. 05-15577, 2007

U.S. App. LEXIS 8595, at *5 (9th Cir. Apr. 13, 2007) (finding no abuse of discretion in

excluding defendant’s alleged “other acts” of gender discrimination “due to the risks of

inefficiency and confusion stemming from the potential need to conduct mini-trials with regard to

each” allegation); Santrayll v. Burrell, No. 91 Civ. 3166 (PKL), 1998 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 586, at

*8-9 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 22, 1998) (excluding evidence that copyright defendant previously copied

from third parties not in the case). Consideration of Oracle’s alleged use of portions of third party

APIs would require a mini-trial to determine the circumstances surrounding the alleged use of the

APIs and to place that use in its proper context. In addition to analyzing the 37 packages of Java

APIs that Google copied, the jury would have to go through a similar analysis for completely

unrelated products that have nothing whatsoever to do with this case. The jury would have to

consider what portions of APIs, if any, Oracle used; whether they were copyrightable; if they

were copyrightable, whether Oracle had permission to use them; and how they compare to

Google’s copying of the Java APIs. Google’s own expert did not make such an inquiry and it is

too late for him to offer such an analysis now. Oracle should not be forced to spend the jury’s

valuable time addressing these irrelevant issues.

Similarly, allowing into evidence Dr. Schmidt’s seventeen-year-old statement that

interface specifications are not protected by copyright—or similar statements by others—would

be prejudicial and would likely confuse the jury. The jury’s proper source for an explanation of

the law is the Court’s instructions—not a statement by a former Sun employee to a congressional

committee or a statement made in an amicus brief. See A&M Records v. Napster, Inc., No. C 99-

05183 MHP, No. C 00-0074 MHP, 2000 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 20668, at *26 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 10,

2000) (excluding expert report by law professor that “offers a combination of legal opinion and

editorial comment on Internet policy”). Admitting these statements creates the risk that the jury

would give them undue weight, and would follow the former employees’ proposed interpretation

6

of the law instead of the Court’s. Indeed that appears to be the very purpose for which Google is

offering these statements.

Admitting these sorts of statements into evidence would also cause undue delay, as both

sides would need to put in evidence about the context and meaning of the statements. For

example, providing the full context of the telecommunications reform legislation that formed the

backdrop of Dr. Schmidt’s 1994 testimony could take hours.

II. CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above, Oracle respectfully requests an order from this Court

granting Oracle America’s Motion in Limine No. 4 and excluding from trial any evidence or

argument regarding Oracle’s alleged use of third party APIs and Sun or Oracle’s past statements

regarding copyright protection for interfaces generally, including the statements referenced in

Google’s Requests for Admission.

Dated: September 24, 2011

MICHAEL A. JACOBS

MARC DAVID PETERS

DANIEL P. MUINO

MORRISON & FOERSTER LLP

By: /s/ Daniel P. Muino

Attorneys for Plaintiff

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.

7

502

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION

ORACLE AMERICA, INC.

Plaintiff,

v.

GOOGLE INC.

Defendant.

Case No. CV 10-03561 WHA

PLAINTIFF’S MOTION IN LIMINE NO. 5

TO EXCLUDE EVIDENCE AND

ARGUMENT CONTRARY TO

STATEMENTS IN TIM LINDHOLM’S

AUGUST 6, 2010 EMAIL

Dept.: Courtroom 8, 19th Floor

Judge: Honorable William H. Alsup

Preliminary Statement

Oracle moves in limine to exclude any evidence or argument contrary to the statements in Mr. Lindholm's August 6,2010 email, concerning his investigation of alternatives to Java for Android, based on Google's refusal to permit discovery of the facts and circumstances of that investigation.

With knowledge of the specific patents that Oracle claims are infringed by Android, Google

employee (and former Sun engineer) Tim Lindholm [REDACTED] Mr. Lindholm recounted these actions and conclusions in an email to Mr. Rubin on August 6, 2010.

On July 22, 2011, Oracle took the deposition of Daniel Bornstein, Google's Rule 30(b)(6)

witness on the topic of non-infringing alternatives. At the deposition, Oracle counsel attempted to

question Mr. Bornstein about Mr. Lindholm's email, but Google claimed that the email was privileged

and clawed it back. Magistrate Judge Ryu subsequently rejected that claim of privilege, required

Google to return the document to Oracle, and required Mr. Lindholm to appear for deposition. At the

deposition, Mr. Lindholm admitted that he wrote the email, but Google's counsel once again asserted

privilege and prevented Oracle from obtaining any discovery into the details of Mr. Lindholm's

investigation, including the particular alternatives Mr. Lindholm investigated, the license terms he

concluded were necessary, and the accuracy of the statements in his email.

Google may not prevent discovery of the facts underlying Mr. Lindholm's statements in his

email, and then offer evidence at trial that is inconsistent with those statements.

Statement of Facts

On July 20, 2010, Oracle informed Google that Android infringed the seven specific patents at

issue in this lawsuit. (Dkt No. 336, August 19, 2011 Declaration of Fred Norton, Exh. 4 (July 20,2010

Oracle-Google Android Meeting presentation bearing bates numbers GOOGLE-00392259-285).)

Thereafter at the direction of Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin, Google engineer Tim

Lindholm investigated the technical alternatives that Google had to those Java patents. (Dkt No. 316,

August 17, 2011 Corrected Declaration of Tim Lindholm Concerning the August 6, 2010 Email and

1

Drafts Thereof; Declaration of Daniel P. Muino in Support of Oracle America, Inc.’s Motions In Limine

Nos. 1 Through 5 (“Muino Decl.”) Ex. P, August 6, 2010 Lindholm e-mail bearing bates number

GOOGLE-12-10000011.) [REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

On July 22, 2011, Oracle attempted to question Google’s Rule 30(b)(6) witness about the noninfringing

alternatives mentioned in Mr. Lindholm’s email. Before Oracle had an opportunity to do so,

Google asserted that the email was privileged and clawed it back under the terms of the Protective

Order. (Muino Decl. Exhibit R, July 22, 2011 Daniel Bornstein 30(b)(6) Tr. at 186:4-22.)

Consequently, Oracle had no opportunity to question any Google witness about the document until

Magistrate Judge Ryu rejected Google’s claim of privilege and ordered Google to return the email to

Oracle (Dkt Nos. 353, 354), which Google did on August 27, 2011 (Muino Decl. ¶ 17).

On September 7, 2011, Oracle took the court-ordered deposition of Mr. Lindholm.1 [REDACTED]

______________________

1 Google opposed the deposition of Mr. Lindholm arguing that “there is no basis for expanding the

discovery limits to permit the deposition of Mr. Lindholm.” (Dkt. No. 215 at 5-8.) Magistrate Judge

Ryu rejected that argument, and ordered Mr. Lindholm to appear for deposition. (Dkt No. 229.)

2

[REDACTED]

Despite Magistrate Judge Ryu’s ruling that the e-mail was neither privileged nor attorney work

product, and despite the fact that Oracle’s questions expressly concerned Mr. Lindholm’s investigation

rather than his communications, Google counsel asserted privilege in response to every one of these

questions, and Mr. Lindholm refused to answer any of them. (Muino Decl. Exhibit Q.)

Relief Sought

Oracle moves in limine for an order precluding Google, its attorneys, witnesses, and experts

from offering any argument or evidence at trial that is contrary to the statements in Mr. Lindholm’s

August 6, 2010 email and Mr. Lindholm’s August 15, 2011 Declaration. In particular, Google should

be precluded from contesting the following facts from the email and Declaration:

- Mr. Lindholm was investigating and reporting on alternatives to the specific patents that Oracle

asserted were infringed on July 20, 2010.

- Mr. Lindholm had thoroughly investigated all alternatives to the patents-in-suit, and Java

generally.

- As of August 6, 2010, Google had no viable alternatives to the patents-in-suit, or Java generally,

for Android.

- As of August 6, 2010, Google needed a license for Java generally and for each and every one of

the seven patents-in-suit.

- As of August 6, 2010, all of the statements in the Lindholm document were true.

Argument

In the two weeks following Oracle’s presentation regarding the patents-in-suit to Google on July

20, 2010, Mr. Lindholm – a former Sun engineer with expertise in Java, experience with Sun’s

licensing terms, familiarity with Android, and knowledge of Oracle’s specific claims of infringement –

investigated alternatives to Java for Android at the direction of Google’s two senior-most executives,

3

Mr. Page and Mr. Brin. He made an unequivocal report on his investigation to Mr. Rubin, the Google

executive in charge of Android. That report – the August 6, 2010 email – has been produced, but

Google has withheld all details concerning the work Mr. Lindholm performed and the basis for the facts

stated in his email. Fundamental fairness requires that Google not be permitted to block discovery into

the details of Mr. Lindholm’s investigation and conclusions, and then offer other evidence to suggest

that the investigation was incomplete, that his investigation was unrelated to the seven patents–in-suit,

or that his conclusions were inaccurate.

As the Ninth Circuit has held in affirming the exclusion of evidence at trial, “the court may

fashion remedies to prevent surprise and unfairness to the party seeking discovery. For example, where

the party claiming privilege during discovery wants to testify at the time of trial, the court may ban that

party from testifying on the matters claimed to be privileged.” Columbia Pictures Television, Inc. v.

Krypton Broad. of Birmingham, Inc., 259 F.3d 1186, 1196 (9th Cir. 2001) (quoting William A.

Schwarzer, et al., Federal Civil Procedure Before Trial, ¶ 11:37, at 11–29 (2000) (emphasis added).) A

motion in limine is an appropriate means to prevent a party from withholding information in discovery,

only to take a contrary position at trial. See, e.g., Service Employees Int’l Union v. Roselli, 2010 WL

963707, No. C 09-00404 WHA, at *5 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 16, 2010) (granting motion in limine) (“[H]aving

avoided disclosing in discovery the materials sought by plaintiffs . . . , it would be unfair sandbagging

to allow defendants to now assert those same materials as a defense to plaintiffs’ claims”). By invoking

privilege and refusing to permit Mr. Lindholm to answer any questions concerning his investigation and

conclusions, Google necessarily has undermined Oracle’s ability to defend the accuracy of that candid,

internal assessment against any efforts by Google to impeach it. Google simply may not tell the jury

that what Mr. Lindholm wrote in his e-mail was wrong, while concealing the detailed information that

shows he was right.

Recognizing the inherent unfairness of such conduct, courts have precluded litigants from

offering evidence at trial if they prevented inquiry into those issues during discovery. In Galaxy

Computer Services, Inc. v. Baker, 325 B.R. 544 (E.D. Va. 2005), the parties disputed the meaning of

certain notes taken by the defendant’s transactional attorney, Mouer. There, as here, the court had

4

rejected a privilege claim over those notes. Id. at 557. Plaintiff’s counsel asked Mouer to “explain her

notes” and the defendant’s counsel instructed Mouer not to answer on grounds of privilege. Id. at 558.

The defendant later sought to have Mouer testify at trial to explain her notes. The court refused to

allow that testimony, ruling that “to permit Mouer to testify to issues which she refused to testify to

during her deposition based on privilege would allow the Defendants to use the attorney-client privilege

as both a shield and a sword.” Id. at 559. Here, as in Galaxy Computer, Google should not be

permitted to limit Mr. Lindholm’s deposition testimony and then at trial try to explain away the candid

statements he made in his email. See also Memry Corp. v. Kentucky Oil Tech., N. V., No. C-04-03843

RMW, 2007 WL 4208317, at *9 (N.D. Cal. 2007) (based on instructions not to answer questions at

deposition, precluding testimony on “anything that the instruction not to answer fairly covered”);

Engineered Prods. Co. v. Donaldson Co., 313 F. Supp. 2d 951, 1022-23 (N.D. Iowa 2004) (barring

party from introducing testimony at trial on issues the plaintiff had prevented the defendant from

exploring during a deposition by invoking the attorney-client privilege).

Google could have disclosed the details of Mr. Lindholm’s investigation and conclusions, and

litigated those issues on the merits. It chose not to do so, and instead elected to withhold that

information. Google must live with the consequences of that decision. Google should not be permitted

to offer evidence or argument that would contradict the statements in Mr. Lindholm’s August 6, 2010,

email.

Moreover, it is appropriate to preclude not just Mr. Lindholm’s testimony that would contradict

the statements in his email, but any evidence offered by Google that would do so. Mr. Lindholm’s

investigation was not an independent exercise: he was acting at the express direction of the most senior

executives of the company, Mr. Page and Mr. Brin; he was working with other Google employees in his

investigation; and he reported their findings directly to the head of Android, Mr. Rubin. Further,

Google’s assertions of privilege – by clawing back the email during the critical period of deposition

discovery, refusing to allow the document to be used in the deposition of its Rule 30(b)(6) witness on

non-infringing alternatives, and forbidding Mr. Lindholm from testifying about the email, other than to

5

admit he wrote it – have foreclosed inquiry not only into Mr. Lindholm’s conduct, but that of Google

itself.

Finally, the relief that Oracle seeks is narrowly tailored to the specific statements in Mr.

Lindholm’s email, and the specific lines of inquiry that Google foreclosed. [REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

Google has asserted, and Mr. Lindholm attested in his sworn declaration, that he undertook his